Before we can discuss AIR Help, you need to understand the basics of Adobe AIR. So let’s start there…

What is Adobe AIR?

Adobe AIR (Adobe Integrated Runtime) is an application development technology for creating native desktop executables that can be installed on multiple operating systems. The AIR development technology provides the developer with a rich assortment of user interface components as well as a powerful programming language that can leverage web technologies as well as access to content on the local file system.

The installation of an AIR application requires the prior installation of the AIR runtime. AIR applications and the AIR runtime are conceptually similar to Java applications and the Java runtime; in order to run the application, the runtime must be installed. The AIR runtime is a quick and easy install, and may already be installed on your computer since it is installed along with many current Adobe products. AIR applications are delivered as a file with a .air extension. The same .air file can be installed on Windows, Mac, and Linux systems.

AIR is based on Open Source technologies, including Flex (ActionScript and MXML), WebKit, SQLite, and Flash. Everything that you need to develop and create an AIR application is available as a free download from adobe.com (Flex and AIR SDKs). Because AIR applications are Unicode enabled, they support all languages, however the current installer supports only 16 languages. The types of applications that can be developed with Adobe AIR are essentially unlimited. Adobe provides the Adobe AIR Marketplace where people can offer their AIR applications to others.

What is AIR Help?

AIR Help is a term that refers to any user assistance application created with the Adobe AIR development technology. In practice, this is more of a concept than a tangible thing. Because AIR is so flexible, each Help system developed using this technology may provide very different features. Unlike some Help technologies, when someone says they’ve got an AIR Help system, you really have no idea what features that Help system may have. The functionality common to all AIR Help systems is that they are all locally installed on the end user’s computer. Remember that AIR is a technology for creating desktop applications; AIR is not installed on a server and although an AIR application can leverage web technologies it is itself not a web application. You might think of AIR Help as a highly customized web browser (although, for some situations it may be designed to limit access to the local file system).

I coined the term “AIR Help” in 2007 after learning about Adobe’s new AIR technology. Because of the relative ease of development and the ability to incorporate web and local file system components, AIR seemed like the ideal platform for the development of user assistance applications.

There are currently two commercially available tools for creating AIR Help, Adobe’s RoboHelp 8 and MadCap Software’s Flare 6 (also Flare 4 and 5). Adobe also provides a utility called RoboHelp Packager for AIR, for creating AIR Help from RoboHelp 6 or 7 webhelp files. If the features offered by the commercial tools don’t provide the functionality that you’re looking for, you can create your own custom AIR Help system. Sample custom AIR Help prototypes are available from leximation.com. Leximation is also developing a DITA to AIR Help plugin for the DITA Open Toolkit as well as a utility for creating AIR Help from CHM (HTML Help) source files.

I’m hoping that other Help Authoring Tool vendors will throw their hats into this arena and show us what they can do with AIR. If you’re using a HAT that doesn’t export to AIR, tell them that you’re interested in seeing what they can do with this technology.

Benefits of AIR Help

As mentioned earlier, AIR Help is cross-platform, so you can install the same .air file on Windows and Mac systems as well as a number of Linux distributions (Fedora, Ubuntu, and OpenSuse). (See adobe.com for details on system requirements.) The AIR Help package is contained within a single .air file, making it easy to deliver to end users. AIR provides a built-in update mechanism. This means that you can ship an early version of your Help, then once the documentation is complete you can upload the updated .air file to your website, and your users will be notified that a new version is available. The update process is quick and easy.

AIR provides an embedded browser component that is built from WebKit (the technology underlying the Safari browser). HTML content that is rendered in an AIR Help system will use this browser instead of one that’s installed on the user’s computer. This means that any CSS and JavaScript that you use in your HTML only needs to be designed for that one browser, WebKit. No need for “browser sniffing” code, and no need to worry about testing on multiple browsers. To me, this is a HUGE benefit of AIR Help over other user assistance options. If you’re currently delivering a “webhelp” system, you probably spend a lot of time developing for and testing on multiple browsers, then get a little worried when another browser comes out that you haven’t tested on. With AIR Help there’s no need for that extra time or worry.

AIR provides many features that make it easy to seamlessly leverage web-based content and data. And because AIR can read from (and write to) the local file system, if you’ve created a custom AIR Help system, it could be designed to monitor the current state of your user’s interaction with the software application you’re documenting. With a custom AIR Help system you could also perform dynamic filtering of content based on the user’s role or input. This has the potential to provide truly a useful, interactive, and intelligent Help system, something people have been striving for since online Help was invented.

All AIR applications must be digitally signed by the publisher. This is seen by some as an annoyance, but really isn’t that big of a deal. During development, you can use a “self-signed” certificate, and when you’re ready to ship, you just need to purchase a certificate from one of the many certificate vendors. An AIR code-signing certificate costs $150 or more per year, and gives your end users the comfort of knowing where the application actually came from.

Last but not least, because AIR is built on Open Source technologies it costs nothing to start exploring custom AIR Help development. Serious development is typically done with Adobe’s Flash Builder (previously called Flex Builder), but it’s easy to get started using just a simple text editor. There are other development environment alternatives such as Aptana Studio that may be worth looking into.

Adobe RoboHelp AIR Help Output

Adobe RoboHelp 8 natively exports an AIR Help deliverable that provides many nice features without the need to do any coding or development. It provides all of the typical features that you expect in an online Help system, such as Contents, Index, Search, Glossary, Favorites, Print, and Forward/Back buttons. It supports context sensitive Help calls, and offers a handful of skins and themes to customize the appearance. The search results include a snippet from the topic (like Google) to provide additional information. The AIR-based auto-update feature is available, as well as the ability to include additional web-based content on Resource tabs and via an RSS feed. One fundamental feature that is lacking is window size and position persistence; when I position my Help window, I like to see it appear at the same location and size the next time I run Help.

RoboHelp’s AIR Help also provides a comments feature that allows end users within a domain (those with access to a common shared server) to share notes on the topics. These notes display combined in a panel at the bottom of the Help application. You can also make use of this comments feature during development as a review tool. Reviewers make notes on topics, then send you the comments XML file. You are able to review all of the comments from all reviewers and make corrections as needed. As you navigate topics, a mini-TOC panel displays links to the sub-headings within that topic. This is a great little feature that simplifies the authoring process as well as making it easier for users to navigate longer topics.

Even though AIR Help provides Help as a single deliverable, once installed the HTML and other system and support files are typically loose in folders within the application installation directory. RoboHelp offers an option to install a single file Help package as opposed to the loose HTML files. For those people still using RoboHelp 6 or 7, Adobe offers a free utility for creating AIR Help from a webhelp project; RoboHelp Packager for AIR.

MadCap Flare AIR Help Output

MadCap’s Flare 6 natively exports an AIR Help deliverable. Flare’s AIR Help is what I call a “wrapped” webhelp system. All of the features in this Help system are HTML-based, and does not take advantage of programmatic Flex or ActionScript coding. Basically, whatever features you can include in their webhelp output, you can include in their AIR Help output.

The standard AIR Help output includes the common features such as Contents, Index, Search, Glossary, Favorites, and Forward/Back buttons. Additional features like including web content or RSS feeds can be included by modifying the underlying webhelp project. MadCap does offer a Feedback Server application that can be used to provide a nice comment/feedback user experience. Unfortunately, Flare’s AIR Help does not provide the auto-update feature, and as with the RoboHelp AIR Help, Flare’s AIR Help window size and position are also not persistent.

Custom AIR Help Options

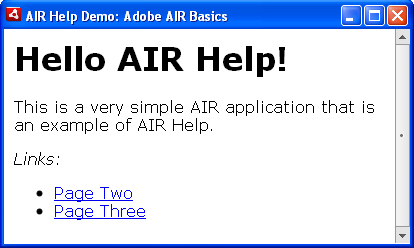

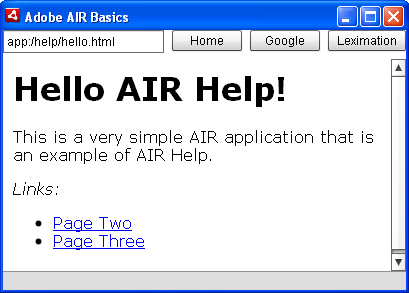

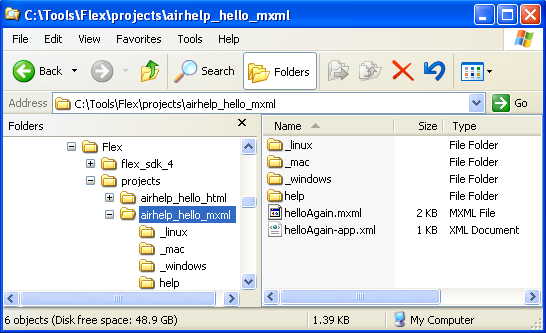

If you’re looking for features beyond those offered by RoboHelp or Flare, you’ll need to develop your own AIR application. There are two basic types of AIR applications, an HTML-based application or an MXML-based application.

For a user assistance application the HTML-based approach works well if you’d like to create a “wrapped” AIR Help system from an existing webhelp project. In general, you should be able to wrap your current set of HTML files and wrap them in an AIR container. This will let you leverage your existing Help development and take advantage of AIR’s embedded browser and simplified packaging and delivery options.

In order to make use of the programmatic controls and interface widgets provided by Flex and AIR, you’ll need to develop an MXML-based AIR application. MXML is an XML format used to arrange user interface components, similar to the way you can build an input form using HTML. In this type of application, ActionScript is used to handle events and dynamic interaction with the interface components. ActionScript is an object oriented programming language similar to JavaScript. Your application can be designed to take on the operating system’s look and functionality for the window elements, or it can be customized. You can even create windows that are a shape other than a rectangle.

Leximation is developing some AIR application code that provides the standard Help system features. This code is intended to be used as a framework from which people will customize, modify, and extend to develop a Help system that’s ideal for their users and products. These features include the standard navigation elements of Contents, Index, and Search, plus Forward/Back, Next/Previous, Home, and Sync with TOC buttons. Options include Auto-Sync, Keep on Top, and Check for Updates. The search functionality includes the ability to search a “remote” index, providing links to web-based content from a local search. This remote index can be generated from content such as your user forums or knowledge base articles, and can be updated daily or as needed. And as you might expect, this AIR Help application does provide persistent window size and position. Samples of prototype AIR Help files are available for download from leximation.com, most include the source files for you to experiment with.

Possible extensions to this framework might include, a commenting or feedback system, a topic rating system, or a chat module that lets users of your Help system chat with others. You might even set up a feature that lets end users extend and customize the Help system in certain ways. It’s even fairly easy to add a Twitter feed or allow the user to actually post tweets from AIR Help.

Leximation’s AIR Help framework will be available as a DITA to AIR Help plugin for the DITA Open Toolkit and as a utility to generate AIR Help from a CHM (HTML Help) project. If you’re interested in beta testing either of these options, please contact Leximation.

The Choice is Yours

Whether you choose to use a commercial tool to build your AIR Help or decide to try the custom route, using Adobe AIR as your Help delivery option can provide your users with a more interactive and useful user assistance experience. You might even find that AIR helps to blur the lines between your software application and online Help, and might just make your Help more helpful.

–Scott Prentice, Leximation, Inc.