Despite the fact that FrameMaker was one of the first authoring tools to support structured authoring (FrameBuilder and SGML in 1991 then FrameMaker and XML in 2002), it is still seen by many as purely a book authoring and publishing tool. While it excels at long document production and provides excellent page layout and formatting capabilities, it also offers a robust XML authoring interface and related features. However, in the XML community, it’s generally not taken seriously as an XML editor. The release of FrameMaker 11 may start to change this perspective.

Despite the fact that FrameMaker was one of the first authoring tools to support structured authoring (FrameBuilder and SGML in 1991 then FrameMaker and XML in 2002), it is still seen by many as purely a book authoring and publishing tool. While it excels at long document production and provides excellent page layout and formatting capabilities, it also offers a robust XML authoring interface and related features. However, in the XML community, it’s generally not taken seriously as an XML editor. The release of FrameMaker 11 may start to change this perspective.

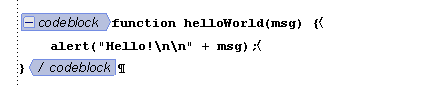

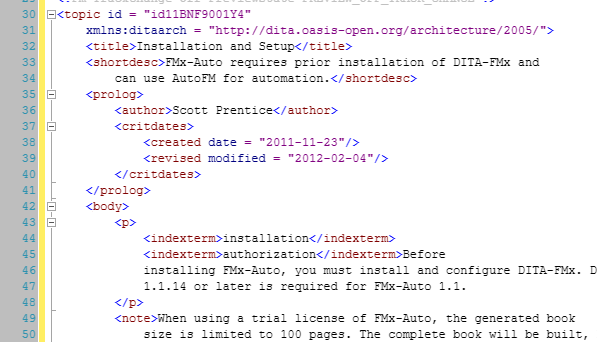

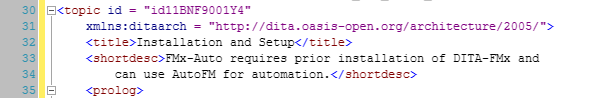

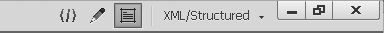

One of first things that people may say when asked about FrameMaker and XML editing is, “you can’t see the angle brackets, so it’s not an XML editor!” Well, with FrameMaker 11, you now have a real Code view authoring option. This isn’t just a simple text editor, it’s a real XML code editor with many of the productivity features you’d expect in a professional XML editor.

FrameMaker 11 is packed with lots of features, for both structured and unstructured authoring. In this review, I’ll just be focusing on the structured authoring and XML features. I was involved in the FrameMaker 11 prerelease testing, and have had the opportunity to offer suggestions and report bugs during the development cycle. I’m quite pleased with the way this release has turned out, although I am one of those people who always wishes that the “bake time” was just a bit longer.

Performance is always on the list of new features. Adobe claims that DITA maps and topics open faster in FM11. To be honest, with my working files I’m not seeing a significant change from FM10, although we’re talking about an open time of a few seconds, even for large maps, so I wouldn’t expect much improvement there. In tests of extreme cases of element use, I do start to see some significant improvement with FM11. I’m seeing a decrease in file open times of up to 92%; that’s a pretty significant change. One document (100 pages with very dense use of inline elements) took over 7 minutes to open in FM10, and only 36 seconds in FM11. Wow. While this test may not represent real-life content, it does show that some serious work was done to speed things up.

Smart Paste is a new feature that lets you copy and paste from HTML or other rich text sources like Word, and automatically have the styles converted into your structured model. FM11 comes pre-configured to support Smart Paste into DITA, but you can customize this feature to work with any data model. This will be a huge time savings when migrating existing content. The resulting element structure may not be exactly what you want, but it’s much better than the old way of copy and paste. I think that this will be a very popular feature.

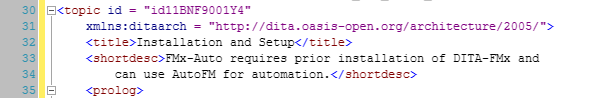

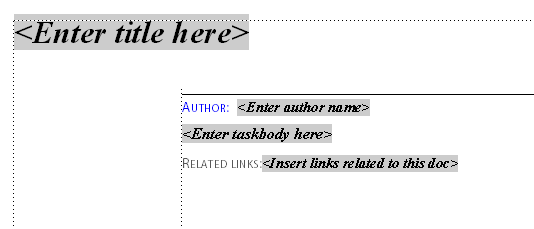

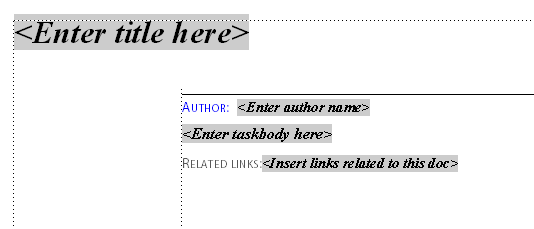

Banner Text is a new feature that provides a clickable label text in newly inserted elements to help guide the author as to the type of content to place in an element. Values such as “title text” or “list item” are defined in the EDD, and you can change them to suit your needs. When combined with the ability to set up boilerplate (or “straw man”) content through the use of the element auto-insertion feature in the EDD, you can make it much easier to start writing a new topic, and will make it easier for people to get more comfortable with structured authoring. The default DITA templates are set up this way.

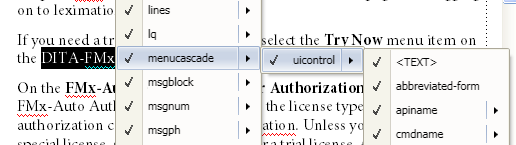

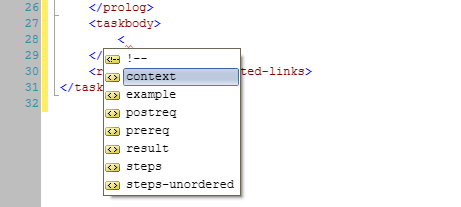

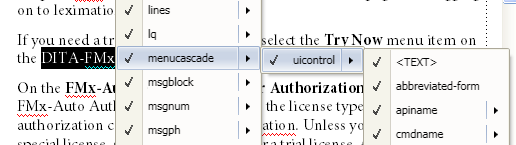

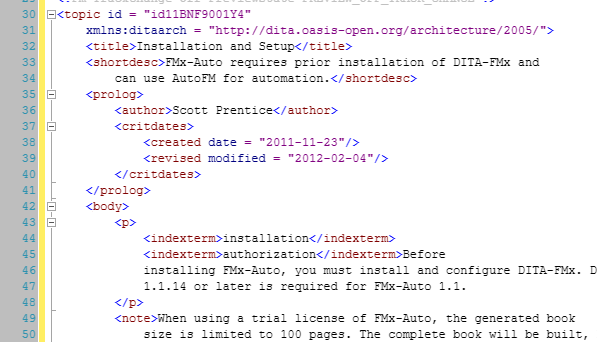

Authoring of structured documents (and XML files) has been made even easier through some new keyboard shortcuts. Pressing CTRL+1 displays a popup list of all valid elements at the current insertion point. Not only can you easily select an element to insert, but this list also lets you select multiple levels (as deep as the model supports) of child elements so that with one click you can insert many levels of nested elements. CTRL+2 does the same thing but lets you wrap the current selection with the selected structure. CTRL+3 provides a change option. CTRL+7 gives you quick access to setting an attribute value. I love the ability to insert multiple elements with one click!

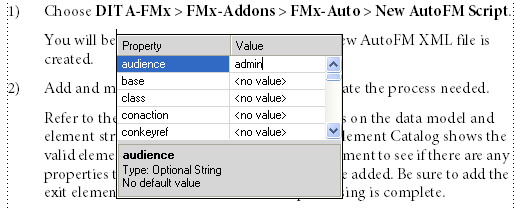

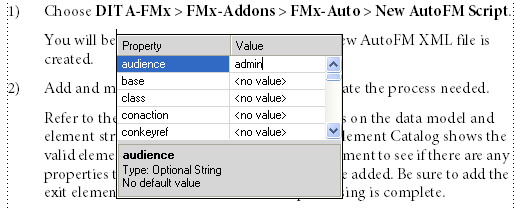

Another great new keyboard shortcut displays an inline attribute editor. Use Esc,i,a,e to pop up a small window that allows selection and entry of attribute values at the current insertion point. Yes, that’s a bit of a long “shortcut,” but you’ll get used to it!

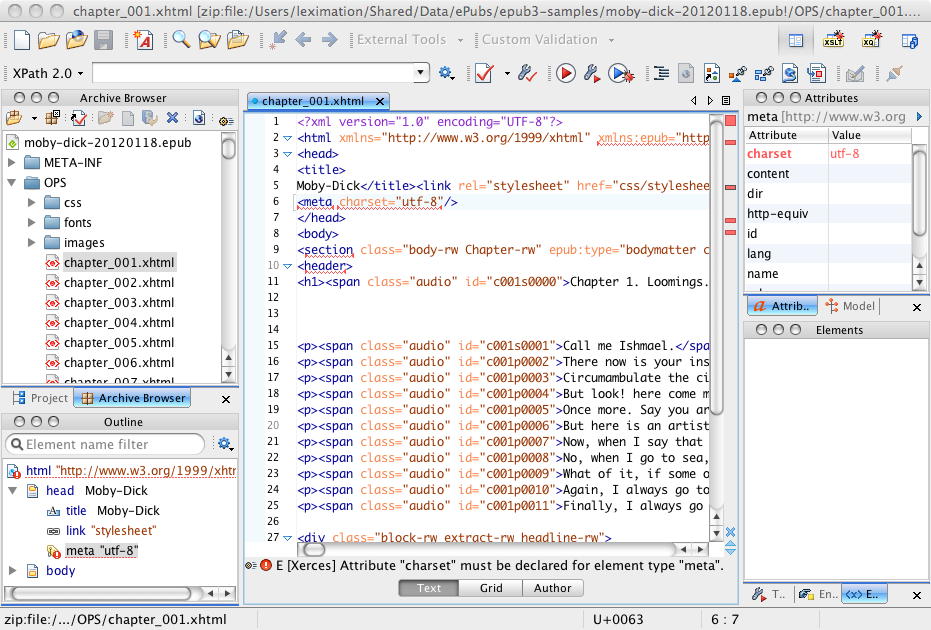

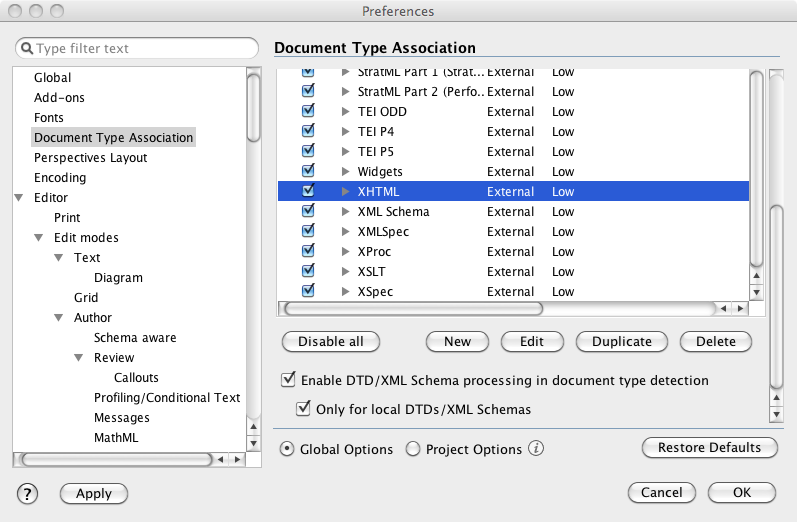

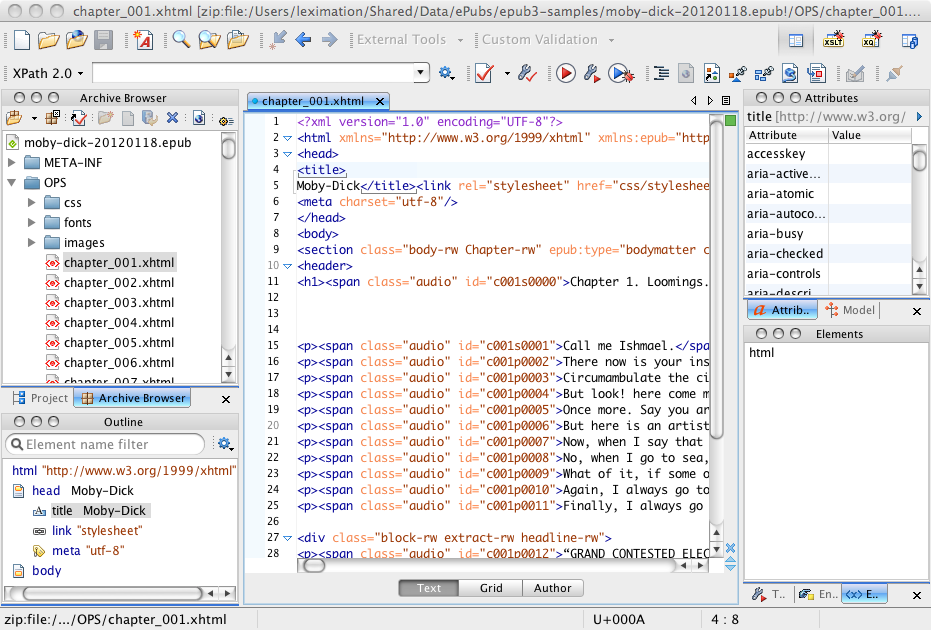

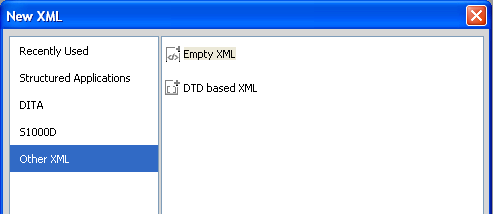

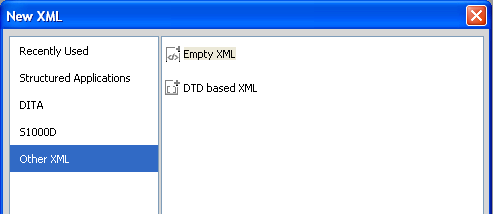

Now you can easily author XML files without creating a structure application. One common complaint about using FrameMaker as an XML editor was the belief that you had to create a structure application in order to edit an XML file. Although this wasn’t strictly true, it wasn’t entirely obvious how to work with XML files without a structure application. Now one of the New File options is “Empty XML,” which is just that, an XML file that isn’t linked to a DTD or structure application. You can quickly create an XML file of any arbitrary model, or one that’s linked to a DTD for validation, but no structure application is required. You can also open up and edit any XML file, as you’d expect from an XML editor.

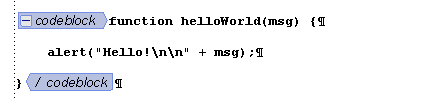

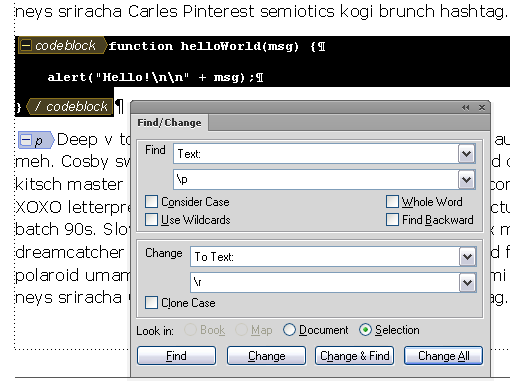

Whitespace handling has been greatly improved. Because the Code view mode includes a pretty printing option, the system is designed to handle pretty printed content without trouble. In the past it was often problematic when you were working in a mixed editor environment, and some people pretty printed their content. This should no longer be a problem!

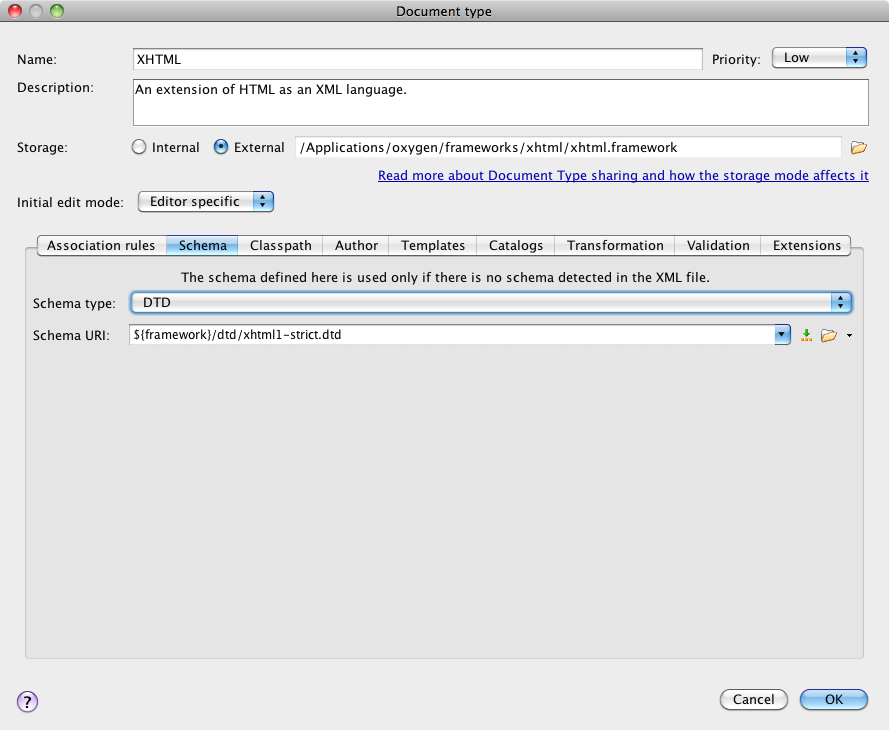

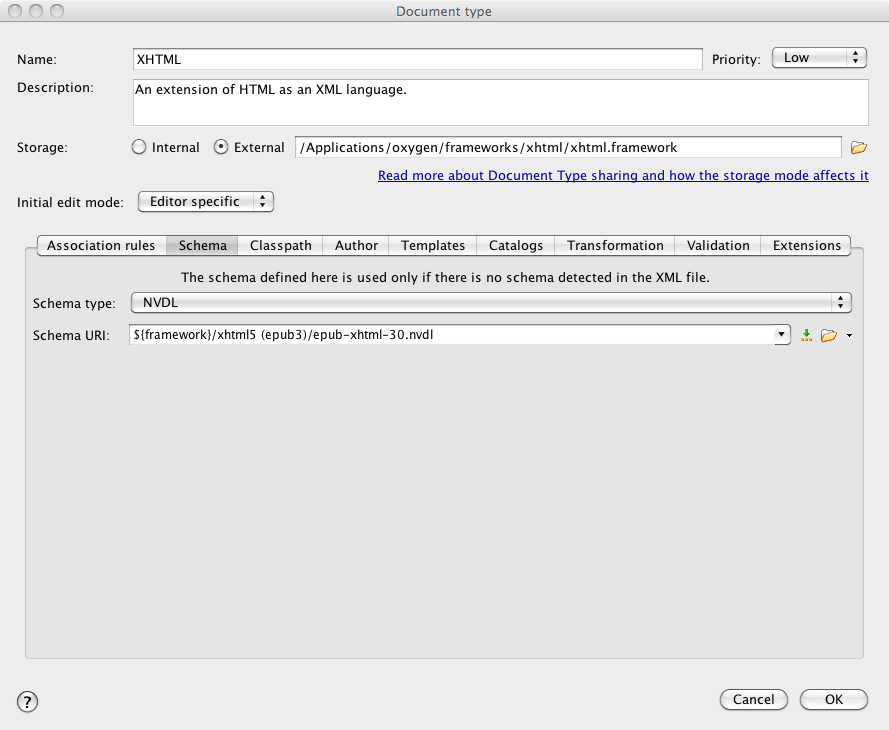

FrameMaker adds two new authoring views in addition to the standard WYSIWYG view. You can now work in “Author mode,” a stripped down WYSIWYG view, which lets you focus on the content rather than thinking about the formatting or page layout. You can also work in “Code view,” which provides access to the underlying XML coding if you prefer to see the “real” XML under the hood.

Code View!

Providing a Code view option in FrameMaker is huge. It’s definitely not something that all FrameMaker users will use, but there are times that you really do need to modify the underlying XML coding, and this provides you with that option. There are people who are more comfortable editing code directly, and this lets them do that right inside of FrameMaker. No need to use another XML editor just because you want access to the XML coding. What’s nice is that FrameMaker remains in the authoring mode you last used. So if you’re in Code view, and you quit for the day, when you come back the next day and open an XML document, it’ll start off in Code view.

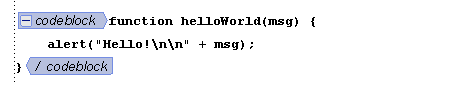

Code view has all of the productivity enhancements that you’d expect in an XML editor. Standard features like line numbering, syntax coloring, and code folding, make it very easy to work with large documents. Also, as you type, you are presented with auto-suggest popups for element and attribute names as well as automatically adding the closing element tag. Because of the runtime XML validation, any invalid coding is indicated with a squiggly underline as well as being reported in the Errors panel, if that is enabled (View > Pods > Errors).

Code view also offers an XML Tree view pod. This is a simplified version of the standard Structure view pod available in the WYSIWYG view, but is really just used for easy viewing and selection of element groups. Unfortunately, you can’t use this view to move elements, maybe in an update?

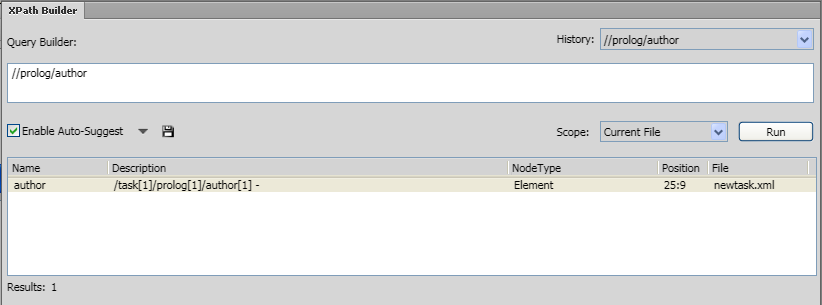

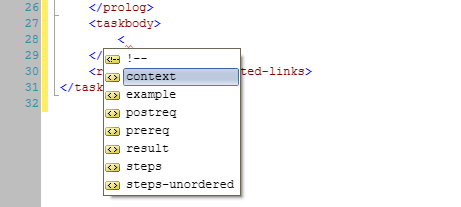

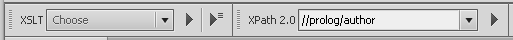

Code view also provides an XPath parser to allow flexible searching in the current file, all files in a map, or all files in a folder. This will greatly simplify the process of locating that content that you know is somewhere on the file system. Once authors get comfortable with basic XPath syntax, this will be very popular. It would be great to see this method for searching for files available in the other authoring views, not just in Code view. One caveat, which will hopefully be fixed in an update, if you perform an XPath search on a folder, you’ll get errors for files in that folder that are not parsable, such as FM binary files. Not a big deal, just a little annoying, since you’d expect it to just skip those files silently.

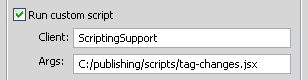

In addition to XPath support, Code view also provides the ability to run an XSLT transformation on the current file, all open files, or all files in a folder. You can create XSL scripts that perform various operations, and just pop over to Code view to run the script as needed. Granted, not all FrameMaker users will be writing their own XSLT scripts, but once they start to see the power behind it, more people will give it a try.

Yes, there are a couple of problems in Code view:

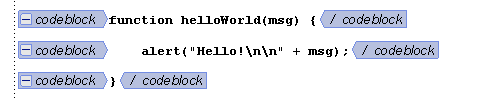

Preformatted content can run into trouble when passed through the Code view. If you’re working with a data model that includes elements like a <codeblock> or <pre>, the content in those elements should not be indented via the pretty printing process. Unfortunately, in FM11 it currently is, which will likely cause formatting problems in your output. I’m hoping that this is something that will be addressed in an early update, but until it is you may want to avoid opening files in Code view that contain preformatted elements.

Another problem with Code view is one that affects older systems that have a single single processor core (or virtual machines with only one core assigned). If you’re one of these groups you can pretty much forget about using Code view in any useful manner. Apparently the XML validation requires two processor cores, so systems with one, will notice a serious lag time between keypresses. This can be mitigated by selecting “No Application” for the structured application name, but that’s not really a good solution in the long run. While this should only affect a small number of people, it’s pretty serious if you’re one of those people. I’m personally hoping that this is at the top of the “fix” list.

DITA Support

As with the previous release, FrameMaker 11 continues to support the DITA 1.2 specification (as well as DITA 1.1). A number of fixes have been made that make it easier to work with FrameMaker in a mixed editor environment and issues have been resolved that created potentially non-compliant DITA topics.

URI notation (for href, conref, etc. attributes) now properly uses the forward slash as the directory delimiter instead of the backslash. A setting in the Options dialog controls this feature. Make sure that “URI Notation for Paths” is selected, and your files will be compliant in this regard.

Cross-reference format names are now stored in the xref/@outputclass attribute rather than the @type attribute, making this feature compliant with the DITA specification. When opening topic files created in earlier releases of FM, your format names will be migrated to the proper attribute. However, note that migrated topics will contain both attributes going forward unless you do something to strip out the @type values. It seems like you’d want the invalid values removed from the @type attribute (so it could be set to the value of the target topic type), but perhaps this will make for an easier transition from earlier versions of FM since it will continue to work properly in both environments. If you are migrating to FM11 and not planning to go back to editing topics in earlier versions of FM, you should set up a script of some kind to strip out the old @type values. (This might be a good use of the new XSLT transformation feature!)

By default, maps open in the Resource Manager, which makes for a very nice map editor. While this is a very useful and efficient view for most map editing operations, such as inserting and arranging topics, it does not yet allow for editing of relationship tables. You’ll need to switch to Document view for that (same as in FM10). Also, the new cool keyboard shortcuts for working with elements and attributes (described earlier) don’t seem to work in the Resource Manager. When you do switch your map to Document View, you’ll see an odd looking structure with your topicref titles shown twice, once for the clickable label and once for the navtitle element. Would be nice to get this cleaned up at some point.

Unfortunately, frontmatter and backmatter elements are not supported in FM11. When you try to insert a <toc> or <indexlist> element in a bookmap, you’ll be required to specify a target file. Because these elements represent generated lists, there’s typically no reason to specify a target file. Add this to the list of things I hope are fixed, sooner rather than later.

DITA map publishing has been greatly enhanced. Now when you save a DITA map to a book with components, the resulting files will have the pagination and numbering applied and any generated files will be included (TOC, Index, etc.). These properties are defined in the ditafm-output.ini file (found in %appdata%\Adobe\FrameMaker\11). This INI file also lets you specify that the “chapters” are aggregated FM files rather than multiple FM files as nested topics (GenerateFlatBook=1), as well as other options for controlling the output. The enabling of generated lists is done through this INI file as well, which is a bit odd, since the DITA bookmap structure provides a perfectly nice model for this purpose. In fact, if your bookmap does specify frontmatter and backmatter, this will be ignored, and only the lists defined in the INI file are used.

I think that the enhanced map publishing is a big step in the right direction, but it falls short of being as useful as it could be. For one, there’s only one INI file. This assumes that all of your books use the exact same properties and generated lists, which is likely not the case. Also, it’s a shame that the generated lists aren’t enabled by the existence of the associated frontmatter or backmatter elements in the map being processed. Finally, it would be really nice if this INI file was to some degree exposed through a user interface, frequently editing an INI file is a bit cumbersome.

Summary

In my opinion, FrameMaker can now be considered a full featured XML editor. That combined with its ability to perform impeccable page layout functions, makes it the ideal authoring and publishing tool for all types of documents and workflows. If I could have only one editor, FrameMaker would certainly be that tool. If you’re an existing FrameMaker user, you should definitely download the trial or give this new release a test drive. If you’re in the market for an XML editor, don’t rule out FrameMaker before you try it; compare the features and benefits of FrameMaker with other XML editors, and you may see that it’s quite the worthy competitor.